Becoming a majolica expert takes practice and patience!

When it comes to buying majolica, each collector, of course, must determine his or her own particular preferences and price ranges, but certain guidelines should be followed in all cases. This is particularly true when considering a purchase at a majolica dealer’s booth or when suddenly attacked by “auction fever.”

When it comes to buying majolica, each collector, of course, must determine his or her own particular preferences and price ranges, but certain guidelines should be followed in all cases. This is particularly true when considering a purchase at a majolica dealer’s booth or when suddenly attacked by “auction fever.”

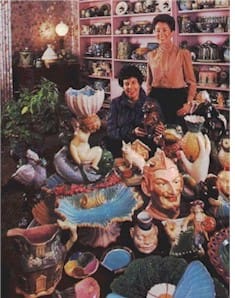

The picture at the left is Marilyn Karmason seated, and Joan Stacke surrounded by some of their two thousand favorite things.

A potential buyer should first carefully note the condition of the majolica. Chips, cracks that go through the piece, and crazing may be hard to accept. Glazing that is dull, or does not conform to the outline of the design, or that looks “heavy” and over painted, is not going to enhance a collection. The undersurface of a majolica piece is almost always glazed; if it isn’t, be wary.

Inexperienced collectors who cannot spot a repaired piece when they see one, or who don’t know if the piece is reasonably priced or not, would do well to deal only with a dealer they can trust.

Some collectors will buy only perfect pieces. And yet, any of us may still find ourselves carried away by a piece that has a chip (it can always be fixed!) or a piece that has been repaired (a “museum-quality” repair, no less!) or a piece that will require taking a chunk out of next week’s food budget (I should lose some weight, anyway!).

Most collectors recall making trips and bringing home a piece of majolica as a prize. Or many enjoy using pieces of majolica to express hospitality. Most of all, there is delight in arranging majolica throughout the house, so that each view of beauty and whimsy will bring a new sense of excitement and pleasure.

Collectors can become familiar with the works of different manufactures by making frequent visits to antiques shows and auctions and observing as much as possible. But it is also mandatory to learn the marks of the various factories, or to recognize the undersurface glazes in the event of no markings. More research is needed to interpret markings of painted numbers and strokes on the undersurface, as well as the underglazing itself.

The best majolica usually has an undersurface of pink, blue, green, and occasionally white. Some exhibit a finely mottled blue/black or blue/brown, as in Palissy or Minton pieces. Many English pieces with well-glazed yellow undersurfaces are thought to be from Thomas Forester, but many less well-glazed pieces with yellow undersurfaces may be American. Grossly mottled undersurfaces may indicate that the piece is American.

Markings on English majolica may include the name of the factory and the English registry mark. The lozenge-shaped registry mark indicates the date of the patent registration, there to protect the design for three years. Minton and Wedgwood also have date-code symbols to indicate the exact date of the manufacture of each piece, even if it were a repetition of an earlier piece. Minton, George Jones, and Wedgwood marks also include a three-or four-digit number corresponding to the number of the piece in the pattern books. The great ceramic artists also may have signed their pieces, such as Paul Comolera on the Minton peacock.

However, because some artists worked for several firms (such as Hughes Protât, who did work for Minton, Wedgwood and T.C. Brown-Westhead Moore), identification of the firm cannot be made by the name of the artist alone.

How one is to collect majolica depends on taste, income, space, and the ability to recognize the authenticity of a piece. The collector would be wise to be armed with a small library of books that deal with the history and descriptive details of majolica, and also carry about a very comprehensive list of marks of the different potteries.

Most collectors of majolica prefer pieces that are marked, but certain anonymous pieces are also very charming and should never be overlooked.

Marks themselves must be authentic; there have been some marks on reproductions partially obliterated as to appear old. Beware of them!

Beware also of copies (and I do not say “reproductions” here). For the most part, copies are lighter in weight than the authentic pieces, and the glaze does not have the richness of true majolica.

In recent years, there has been an onslaught of day-before-yesterday’s cobalt pitchers on the market that have fooled many knowledgeable collectors and even dealers.

As for modern reproductions, reputable manufactures operating today will mark their majolica with their own factory name and, many times, the date of production. The venerable, and venerated, Minton & Co. celebrated its bicentennial in 1993 with the reproduction of a teapot and will continue to reproduce an additional majolica teapot each year. Production is limited, and each teapot is fully marked to inform the buyer of its origin. Majolica collectors who are lucky enough to own both the original teapot and the modern reproduction of the same design are able to enjoy the contrast between the original majolica and the present-day fine china version.